John and Kay Fox may be the last clients still living in their Paul Kirk-designed home.

When John and Kay Fox decided to build a new house for their growing family, they sought out the best architect they could find. And why not? The year was 1964 and every architect’s fees were set by the American Institute of Architects based on a percentage of the project’s cost. Hiring a great architect cost the same as hiring a good one. They had seen Paul Hayden Kirk’s residences in the pages of Sunset Magazine (the Dafoe House of Longbranch, Washington, made the cover in 1963), and were both long-time fans of modern design.

John had lived in the Tri-Cities area since graduating from Oregon State University in 1951 with a master’s in engineering. He would work for General Electric and Battelle at the Hanford Nuclear Facility before being elected Mayor of Richland. His first house, bought in 1958 when the federal government was selling off defense industry housing, cost $7000. Another government sale of land led the Fox’s to build their Kirk home on the Columbia River.

“Six of us went in together and bid for two tracks of land along the north side of the area,” recalled Fox, now in his 90s. “There weren’t any houses built out there and we won an award and got the tracks of land along the river. The six of us divided the land in 7 pieces, each roughly an acre a piece between the road on the west and the river shore. We sold off one lot and drew lots on the others.”

The Foxes won the southernmost parcel. The city of Richland initially refused to pave the gravel road or provide utilities, and the new landowners had to pay for a water line. A few years later, the city put in a sewer line and paved the street, improvements the landowners paid for over the next decade. The first house was built in 1960 and the Foxes finally went looking for an architect in 1964 when they decided to stay in Richland.

“We had the lot which was a real gift, a joy, and always has been,” noted Kay. “And we wanted something simple and that would work for us and our daughter, and later two boys.”

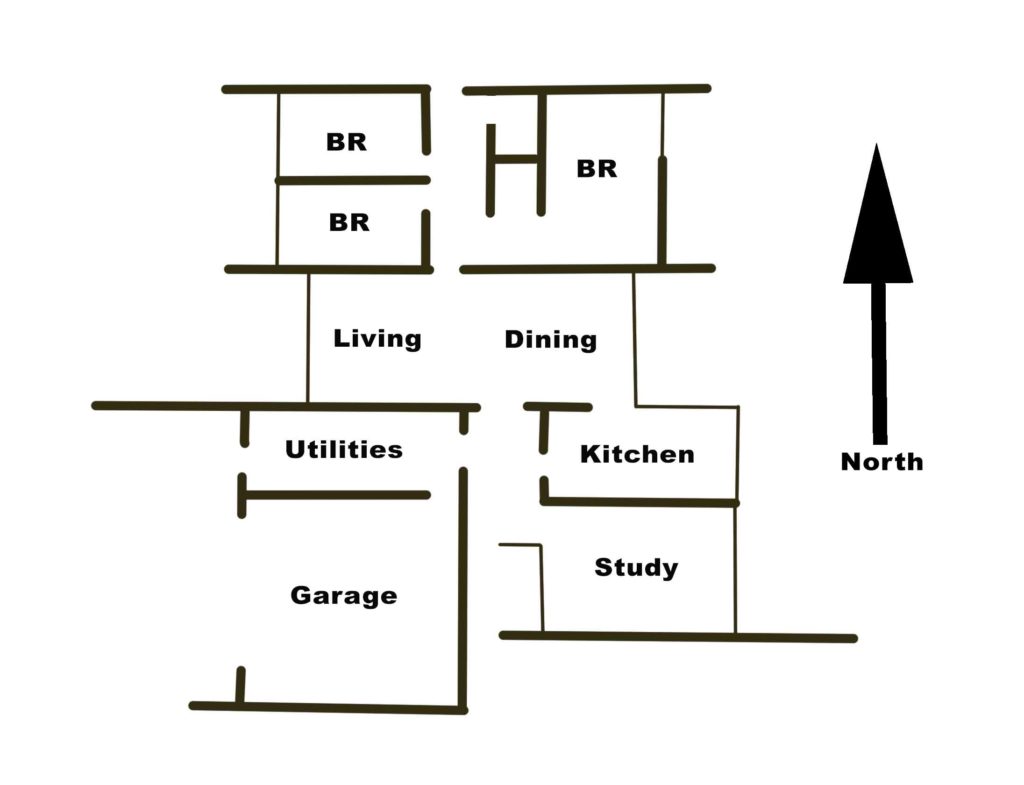

East-west masonry walls extend to provide privacy.

“We were looking at Sunset magazine and Kirk was on the annual review of houses in the early 60s,” John said. “And we looked at what others were building to get ideas. We knew a young kid, a Japanese guy–Ohashi was his name–and he was designing some modern houses for builders here. We had been in one or two of those, but about the time we were getting into this he moved to Spokane.”

The Foxes called Kirk’s office in Seattle and set up a meeting. It wasn’t until Kirk had accepted the project that they realized how busy he was. By the mid-1960s, the firm of Kirk, Wallace, McKinley & Associates had finished large projects for the Seattle World’s Fair, United Control Corporation, Simpson Timber, and the University of Washington. On the drawing boards were dormitories for the UW, and the Jefferson Terrace, Center Park, and Roxbury apartments for the Seattle Housing Authority. Despite these more lucrative projects, Kirk continued to design the small wooden buildings that had made him the most prominent name in Northwest modernism. Smaller designs from the early 1960s included the Japanese Presbyterian Church, the Magnolia Branch Library, and the Simons, Eytinge, and Dorpat residences.

Kirk was too busy to travel to Richland and inspect the site. Instead, the Foxes provided a topographical map and photos. They knew nothing about his disability until they met with him in his office in Seattle’s Eastlake neighborhood. Childhood polio had robbed Kirk of the use of his right arm and impaired his mobility. “I was very surprised, because I didn’t know about his arm,” recalled John. “He had this big brick he kept close to hold things down.”

The Foxes told Kirk they wanted a house of roughly 2000-square feet on one floor, with no stairs or basement, and a two-car garage rather than Kirk’s customary carport. Double-pane glass and a fireplace were essential for Richland’s cold winters, as was air conditioning for the region’s hot summers. Where to site the home took some time to resolve. Some neighbors planned to build near the street, creating a large open expanse toward the river. Others wanted their homes near the river with the idea of eventually selling off the street side portion of the lot.

If the siting took some time to resolve, the design fell quickly into place. Kirk had been arranging residential spaces for 25 years and the Fox design continued his masterful blending of open planning and zone separation. The materials would include concrete block and glass with exterior walls covered in cedar shingles, a material from the Victorian era that Kirk resurrected for the Japanese Presbyterian Church and other designs of the 1960s.

The north and south walls of the home would be solid, made of concrete block in a stack bond pattern (as the walls rose, neighbors wondered if the Foxes were building a car wash). The east and west walls would be largely glass, with minor walls and the surrounding fascia covered with shingles.

The front door didn’t face the street, but was placed on the south side, hidden between the garage and the study. To reach it, visitors pass through an outdoor room–a transition Kirk frequently employed in residential designs–and once inside, there is a choice of taking a hard right into the study, a soft right into the kitchen, or straight ahead through saloon-style louvered doors into the living-dining space.

This room spans the width of the house. The dining area faces the river with access to a covered patio. The living area features a simple fireplace with a long raised hearth. Beyond a wall of glass is a courtyard enclosed with a wood grill that blocks the view from the street and creates an enclosed play area for young children. A door on the far side of these living areas leads to the utility room, three bedrooms and baths.

Kirk’s attention to detail included the kitchen. “I distinctly remember drawing out the kitchen with no cabinets,” Kay recalled. “And he said, ‘Would you please look at the pots and pans you have and take measurements of how big they are and we’ll make drawings so you can put your things away.’ I looked at my pots and pans and took measurements and when the kitchen was done, I brought my things in and for the most part have never changed them.”

Over the past 57 years, the Foxes raised three children and have enjoyed a lengthy retirement in the home, never finding a good reason to significantly expand or alter the design. “It is a small house, but it has worked for us and we love it,” said Kay. “The house worked for us then and works for us today.”